Texan in the Rhodesian Army Says He Fights for Love, Not Money

Written by CAREY WINFREY Special to The New York Times September 2, 1979

MAGUNGE, Zimbabwe Rhodesia, Aug.30 -When Prime Minister Abel T. Muzorewa stepped off a helicopter here this morning to be briefed on guerrilla activity in this remote northern tribal area, the first person to greet him was Joseph Columbus Smith, of San Antonio, Tex.

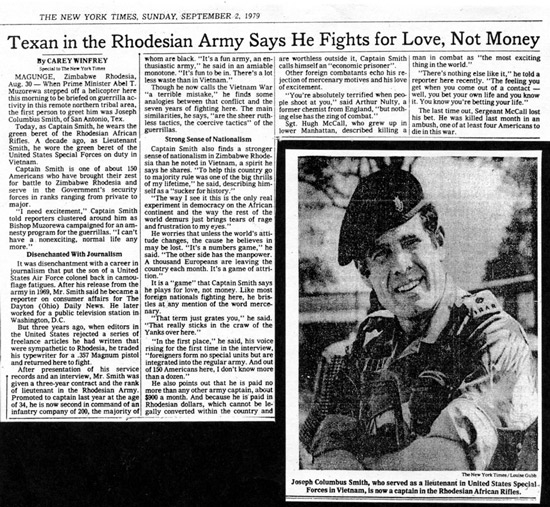

Today, as captain Smith, he wears the green beret of the Rhodesian African Rifles. A decade ago, as Lieutenant Smith, he wore the green beret of the United States Special Forces on duty in Vietnam.

Captain Smith is one of about 150 Americans who have brought their zest for battle to Zimbabwe Rhodesia and serve in the Government’s security forces in ranks ranging from private to major.

“I need excitement,” Captain Smith told reporters clustered around him as Bishop Muzorewa campaigned for an amnesty program for the guerrillas. “I can’t have a non-exciting, normal life any more.”

Disenchanted With Journalism

lt was disenchantment with a career in journalism that put the son of a United States Air Force colonel back in camouflage fatigues. After his release from the army in 1969, Mr.Smith said he became a reporter on consumer affairs for The Dayton (Ohio) Daily News. He later worked for a public television station in Washington. D.C.

But three years ago, when editors in the United States rejected a series of freelance articles he had written that were sympathetic to Rhodesia, he traded his typewriter for a .357 Magnum pistol and returned here to fight.

After presentation of his service records and an interview, Mr.Smith was given a three-year contract and the rank of lieutenant in the Rhodesian Army. Promoted to captain last year at the age of 34, he is now second in command of an infantry company of 200, the majority of whom are black.” It’s a fun army, an enthusiastic army,” he said in an amiable monotone.”It’s fun to be in. There’s a lot less waste than in Vietnam.”

Though he now calls the Vietnam War “a terrible mistake,” he finds some analogies between that conflict and the seven years of fighting here. The main similarities, he says, “are the sheer ruthless tactics, the coercive tactics” of the guerrillas.

Strong Sense of Nationalism

Captain Smith also finds a stronger sense of nationalism in Zimbabwe Rhodesia than he noted in Vietnam, a spirit he says be shares. “To help this country go to majority rule was one or the big thrills of my lifetime,” he said, describing him self as a “sucker for history .”

“The way I see it this is the only real experiment in democracy on the African. continent and the way the rest of the world demurs just brings tears or rage and frustration to my eyes.”

He worries that unless the world’s attitude changes, the cause he believes in may be lost. “It’s a numbers game,” he said. “The other side has the manpower. A thousand Europeans are leaving the country each month. It’s a game of attrition.”

It is a “game” that Captain Smith says he plays for love, not money. Like most foreign nationals fighting here, he bristles at any mention of the word mercenary.

“That term just grates you,” he said. “That really sticks in the craw of the Yanks over here.”

“In the first place,” he said, his voice rising for the first time in the interview, “foreigners form no special units but are integrated into the regular army. And out of 150 Americans here, I don’t know more than a dozen.”

He also points out that be is paid no more than any other army captain, about $900 a month. And because he is paid in Rhodesian dollars, which cannot be legally converted within the country andare worthless outside it. Captain Smith calls himself an “economic prisoner”.

Other foreign combatants echo his rejection of mercenary motives and his love of excitement .

“You’re absolutely terrified when people shoot at you,” said Arthur Nulty, a former chemist from England, “but nothing else has the zing of combat.”

Sgt. Hugh McCall, who grew up in lower Manhattan, described killing a man in combat as “the most exciting thing in the world.”

“There’s nothing else like it,” he told a reporter here recently. “The feeling you get when you come out of a contact – well, you bet your own life and you know It. You know you’re betting your life.”

The last time out, Sergeant McCall lost his bet. He was killed last month in an ambush, one of at least four Americans to die in this war.